The historic Jingu Gaien park area was created 100 years ago through donations from the public to provide a much-needed oasis of greenery in the city center. The park is famed for its iconic avenue of four rows of magnificent gingko trees, as well as thousands of other trees. This area also houses two much-loved stadiums of historic importance to baseball and rugby fans, and some low-cost and free-of-charge sports facilities for the general public.

A large-scale redevelopment project has been planned for the area, through a public-private collaboration between real estate developer Mitsui Fudosan, partial landowner Meiji Jingu Shrine, partial landowner Japan Sports Council (part of the national government), and Itochu, a company which has its headquarters adjacent to the park.

The redevelopment plans involve removing some of the park facilities entirely and shuffling others around to make room for two new high rises to rent as offices and serviced apartments. These will tower over the area.

Itochu will rebuild its headquarters, which is adjacent to the park, at nearly twice the current height (made possible by its purchase of air rights through the project).

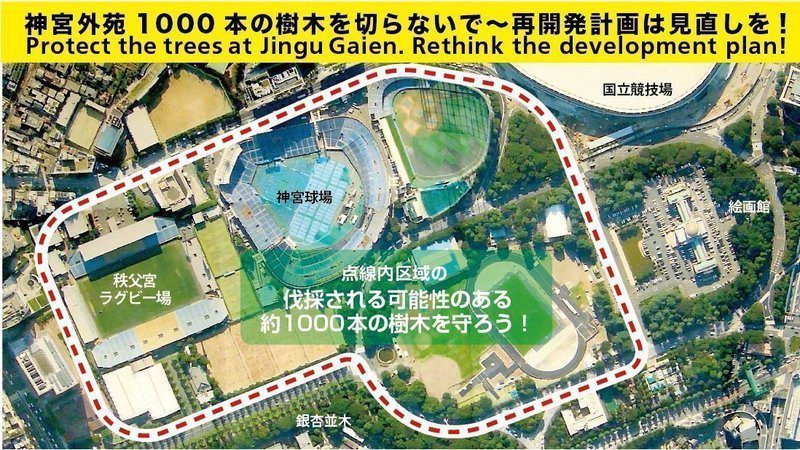

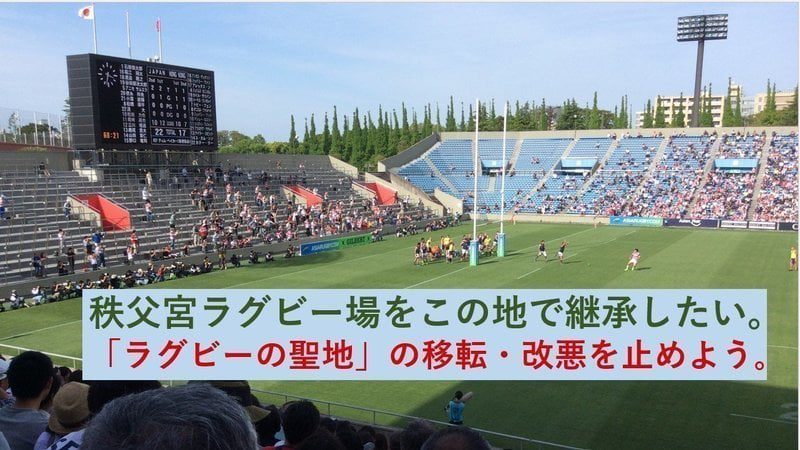

The two stadiums and an expensive members-only tennis club will be rebuilt in new locations, resulting in the cutting down of thousands of trees as well as the wasteful scrapping of structures that could be renovated and continue to be used. The iconic rows of gingko trees will also be endangered by placement of the new baseball stadium just 6 meters from their trunks.

The two stadiums and an expensive members-only tennis club will be rebuilt in new locations, resulting in the cutting down of thousands of trees as well as the wasteful scrapping of structures that could be renovated and continue to be used. The iconic rows of gingko trees will also be endangered by placement of the new baseball stadium just 6 meters from their trunks.

In addition to the loss of greenery, there is also a fairness issue at play here. All of the other public sports facilities currently in the park will be eliminated under this plan, with only the one that caters to the elite remaining.

Experts, including the Japan Committee of the UNESCO-affiliated International Council on Monuments and Sites, have raised concerns about the overall plan and in particular the slipshod way in which the environmental assessment was conducted.

Citizens have raised their voices to demand that the project be canceled or at least re-considered. More than 285,000 signatures have been collected on four petitions protesting the plan (ours and three others). Local residents have even filed a lawsuit. There has been significant media coverage both inside and outside Japan (including in the New York Times), and three Japanese newspapers (the Asahi Shimbun, the Mainichi Shimbun, and the Tokyo Shimbun) have published editorials calling for the development plan to be revised.

A local group centered on parents of children who attend a school adjacent to the park (Volunteer Association to Preserve Meiji Jingu Gaien for Our Children) has also spoken out, with concern of the effect on their children’s rights to a healthy environment, and their rights to a quality education (as learning in a natural environment is a precious experience for children living in an urban area).

A group of university students (Amamo) has also been active in calling for the redevelopment plans to be revised. As members of the young generation, they are especially concerned about how the country is to be developed, because they are the ones who will live in the future of the country. Their voices are often difficult to reach effectively to the politicians who are elected in Japan’s highly-aging society.

The members of the development consortium, as well as the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, have ignored these public voices. They seem intent on foisting the project onto the public no matter what concerns are raised. The absence of stakeholder dialogue is striking.

The project was developed behind closed doors through non-public discussions between the developers and the Tokyo Metropolitan Government with no opportunity for public participation. Even when the project details were announced, the developers did not reveal how many trees would be cut down under the plan. It took Professor Ishikawa of ICOMOS conducting an on-the-ground study comparing the plans to the trees in the park to bring to light the extensive tree felling that would be required.

The project has also been rushed through the approval process. The Tokyo Metropolitan Government’s Planning Commission quickly approved the project after it was submitted, claiming that there had been “sufficient discussion”, when in actuality there had been no public discussion whatsoever, and most members of the public only learned about the project after the Commission approved it. Serious concerns repeatedly raised by members of the environmental assessment committee and by ICOMOS have been brushed aside by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government employees who manage the environmental assessment committee. The Tokyo Metropolitan Government approved the plan even though the head of the environmental assessment committee clearly stated that the committee was “unable to give the plan a go-ahead sign.”

Both Mitsui Fudosan and Itochu make claims about their ESG credentials and commitment to human rights and the UN Sustainable Development Goals, but their behavior on this project tells a different story. The planning for the project was conducted with no chance for the public to participate or express their views, and the companies still have not held sufficient explanatory meetings with local residents, despite many such requests.

This pattern of large-scale developments on public lands leading to large numbers of trees being cut down, favoritism toward profit-making entities over the interests and rights of the public, and lack of opportunity for meaningful public participation in the planning and approval process, is a pattern currently being repeated throughout Japan. Jingu Gaien is the most prominent example, but the same issues play out over and over across Japan due to structural tendencies in how government operates here.

The Jingu Gaien redevelopment project has strong links with the Tokyo Olympics held in 2021. Some say that bringing the Olympics to Tokyo was an excuse to redevelop Jingu Gaien. When the new National Stadium was built for the Olympics, that became the pretext for removing the height restrictions in the landscape preservation zoning overlay over the entire park area, paving the way for the current redevelopment plan. One of the motivations behind the design of the new rugby stadium is to make money to offset the ongoing losses from new National Stadium, which was costly to build and maintain and is seldom used.

To say that this is a reckless plan riddled with problems is an understatement. It is incredible that such an outrageous plan has been approved. But there is still the possibility to get it changed if we as citizens speak up loudly enough. We need to raise our voices and not give up!

This petition asks the Tokyo Metropolitan Government to rescind its approval of the Jingu Gaien redevelopment plan. We believe there needs to be a rethink from scratch about what should be the future shape of Jingu Gaien, that involves the public and experts, and that considers environmental and historical preservation aspects.